Design Operations

Throughout my career, I’ve noticed that gaps tend to appear between what I designed and what got built.

Here are a few causes of those, and some processes I’ve developed to close them.

Problem: Quality management

Most places I’ve worked use a hybrid waterfall/Agile delivery process.

Waterfall methodologies have built-in quality control processes. In Agile, quality is owned by the whole team.

But in hybrid approaches, although there are QA engineers reviewing the details, the overall quality of the product isn’t directly managed by anyone.

This can be a real problem when requirements aren’t pulled through or designs aren’t implemented accurately.

Solution: Close the Loop

Designers need to be involved in writing user stories to ensure that all the requirements are captured.

QA engineers need to be in contact with deisgners so that there’s full visibility across the delivery pipeline.

Project managers need to implement regular and early reviews of work-in-progress code with designers.

Strictly speaking, this is just basic Agile good practice. But when time and budgets are tight, these things often get regarded as overheads rather than investments and fall by the wayside.

Example: GAA Redesign

In Summer 2024 I led a design rework of the Gaelic Athletic Association’s website.

The project manager couldn’t see any value in me attending the daily stand-ups.

Once I’d reassured him that I could hide the hours in my timesheet and wouldn’t be billing them to his budget, he eventually agreed.

As well as the numerous small queries and design issues we addressed, the daily contact created strong relationships with the engineers. They then felt more able to contact me during the rest of the day with questions and suggestions.

The result was a pixel-perfect product.

Problem: Design documentation

In hybrid delivery methods, there can be separation between designers and engineers. The temptation is to try and bridge this with detailed specs.

But if they’re too detailed, specs become unhelpful. They’re cumbersome and time-consuming to manage, and readers miss important details in the mass of annotations.

Solution: Treat it like a product

As a UX designer, I apply the same principles to documenting my designs as I do to creating them. Keep the end-user in mind and actively gather insights and opinions to improve them

Taking a user-centred approach means that I learn how best to hand over designs and where to surface requirements so that they’re easy to consume.

Example: SYZYGY Functional specs

At SYZYGY we were experiencing a high volume of design QA issues in our products.

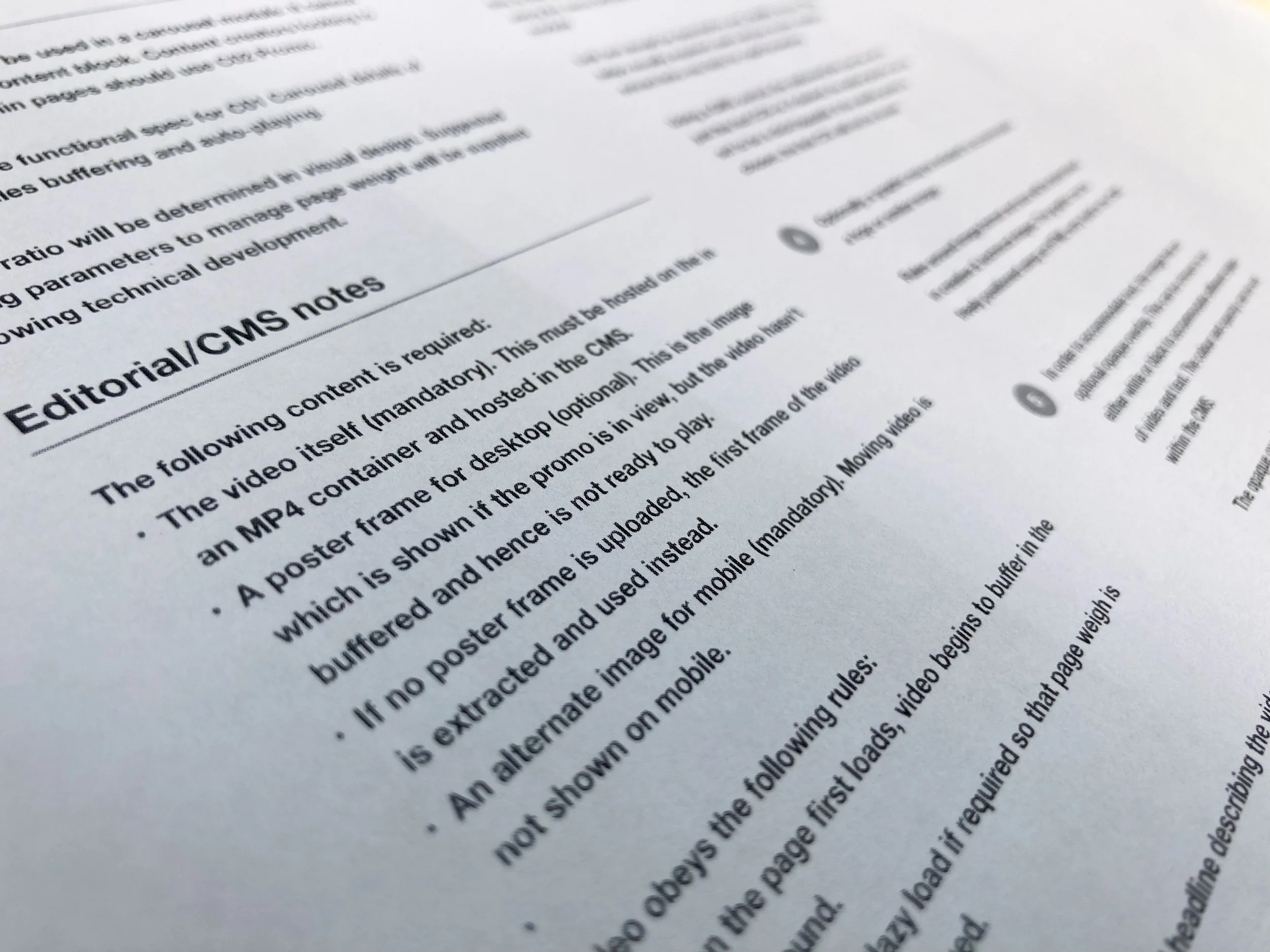

I did some user research among the developers and found that our functional specs weren’t well structured. Everything looked like it had the same priority, and details were being missed because nothing stood out.

So I worked with them to design a new template with annotations grouped according to who would consume them. Then I added clear headings to signpost the content.

The result was a significant decrease in design QA issues, and a closer working relationship with the developers. They appreciated that I’d taken the time to understand their needs.

Example: T.Rowe Price Delivery

While I was at ELSE I worked client-side in investment bank T.Rowe Price. The development team worked on the floor below the design team and this was causing communication issues.

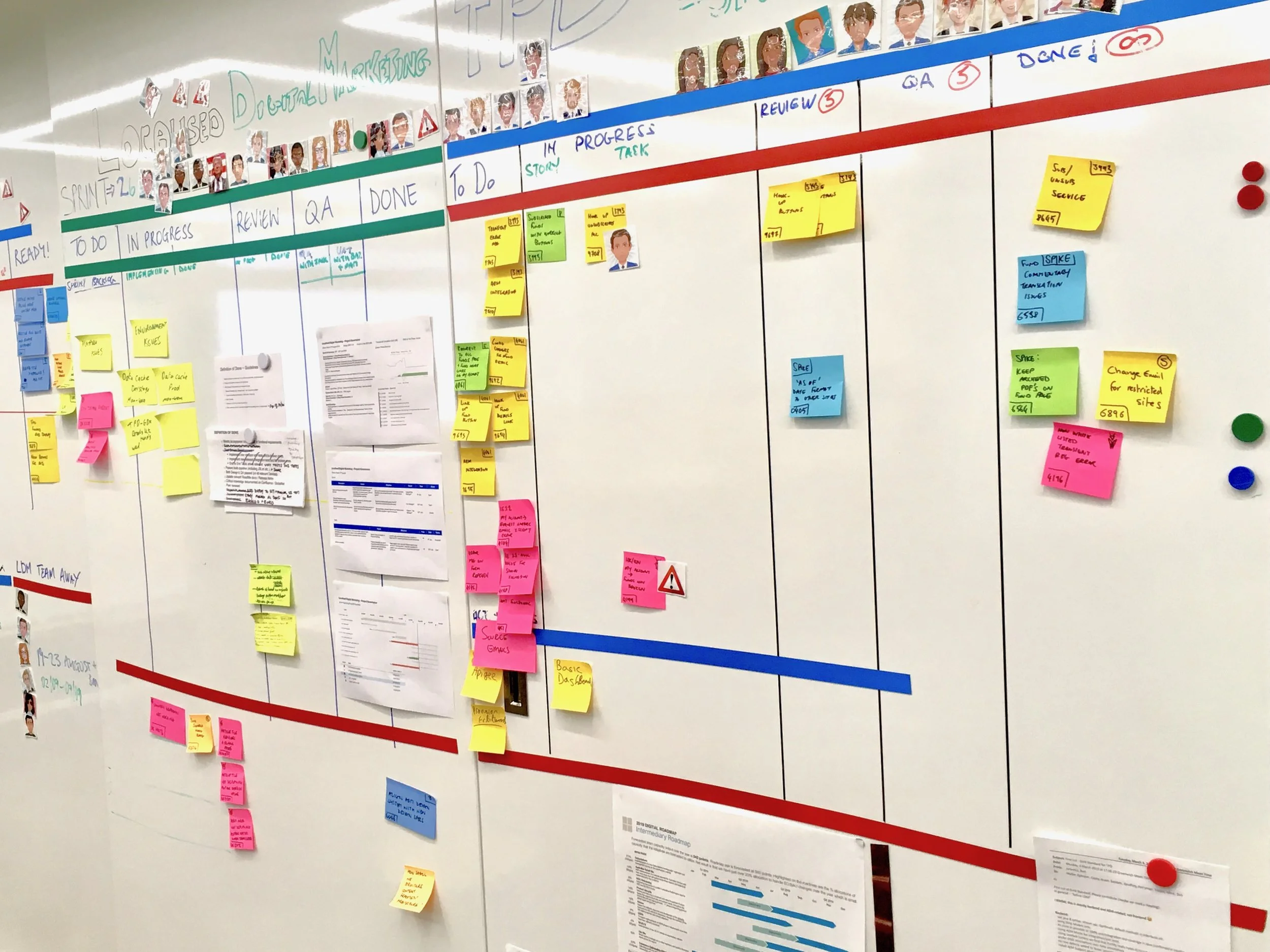

I noticed that there was a large whiteboard behind the developers, so I moved our reference printouts onto that and held our design review sessions there (see image).

Developers couldn’t help but eavesdrop on our discussions and often spontaneously joined in. This created a natural communication channel for very little effort.

Problem: Minimum Viable Products

I have to admit, my heart sinks when people talk about delivering an MVP.

By definition you’re delivering a weaker version of what the client really wants (and probably already has). Apart from increasing the risk of scope creep, that also reduces the impact of the product.

After a long and costly redesign process, clients want to launch their new sites and apps with a fanfare, both publicly and internally to their stakeholders. MVPs naturally mute that ‘ta-da’ moment.

“Broken gets fixed but mediocre sticks.” There are always more pressing things to do than fix something that’s basically working. This often means that design debt run up in the MVP never really gets paid off.

Solution: Plan long, deploy in stages

One problem I’ve seen with the MVP approach is that the team only plans as far as go-live. If you’re going to knowingly deploy a sub-standard product then it’s important to extend the horizon beyond that. This ensures that any debt is properly captured, prioritised and fixed.

One other approach is to avoid a ‘big bang’ launch and deploy the new product in stages. If it’s possible, why not get code live and earning its keep immediately rather than holding things back until everything is ready to go?

Example: GAA Redesign

The GAA redesign was also a technical replatforming as we upgraded the site to a new version of Deltatre’s CMS. Working with the tech lead we developed an approach where we prioritised changes in order of value and deployed them in stages.

This more Agile approach meant that the new designs were out there delivering value, not only to fans and the business but also to the delivery team.

We could harvest data about the impact of the new pages to validate the overall design direction.

Example: Marks & Spencer replatform

One of my client-side roles was as part of the team bringing M&S’s ecommerce platform in-house. This was a long project with a lot riding on it - our first-year target was £800million of turnover.

While the launch was obviously a milestone, the business rightly took the view that it was the start of a conversation with our users. I was part of a team that was already looking beyond go-live.

We’d identified some issues in pre-launch user testing that there wouldn’t be time to fix before the product went live, and so we developed proposals to fix them.

We had some hypotheses from the pre-launch tests ready to roll out as A/B tests. For example, we knew there were issues with the filter drawer in the product listing pages so we prepared variants to test.

We used the private beta phase to refine our analytics processes and dashboards.

Although the optimisations we made were quite small in percentage terms, with such a large turnover even small wins amounted to tens of millions in increased revenue.